In ancient Rome, olive oil was used to dress dishes, light up houses or to take care of your skin in the thermal baths.

“There are two liquids that are especially pleasant for the human body: wine on the inside and oil on the outside. Both are the most excellent products of the trees, but oil is an absolute necessity, and man has not erred in dedicating his efforts to obtaining it”. Pliny the Elder did not err in expressing himself in this way in his Natural History: olive oil was an indispensable product for the daily life of the ancient Romans, who used it not only as an ingredient in the kitchen, but also as fuel for lighting and as a hygienic ointment in the baths. It is not strange that a whole industry of production, commercialization and transport developed around it.

The production of oil in ancient Rome was carried out by the Phoenicians and the Greeks, although it was the Romans who produced it on a large scale and made it something that was habitually consumed by all social classes. The oil was obtained in the villas, rural farms that also used to grow cereals and produce wine.

Production and categories

After being harvested, the olives were stored in the tabulatum, a room with a waterproof and slightly sloping floor on which the olives were placed to release the vegetable water. This dark and smelly liquid, as Pliny himself tells us, could be used as an insecticide, herbicide and fungicide.

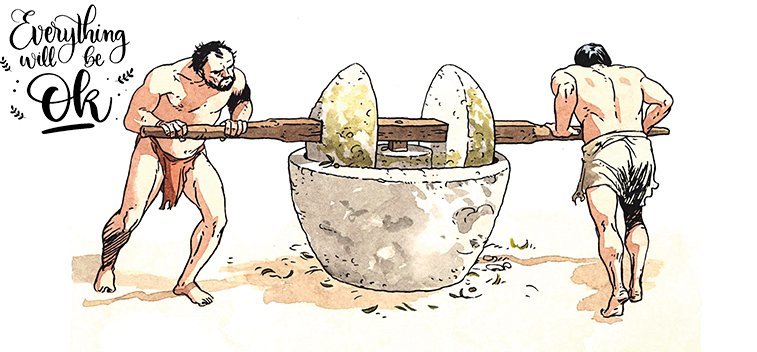

After this step, the olives were milled. The different mechanisms used ground the olives without breaking the stone, since it was considered that this gave the oil a bad taste. The most common grinding system was the trapetum. This large mill consisted of a fixed area called the mortarium and two semi-spherical stones called the orbis, which two men turned over the mortarium by pushing a horizontal axis. This produced an olive paste that was pressed in a room known as a torcularium. In this space was the press (also called, by extension, torcularium), a complex mechanism capable of subjecting the paste to great pressure. The oil thus obtained was decanted into large globular ceramic vessels called dolia, which were usually half-buried, and then stored in amphorae in the so-called cella olearia.

According to its quality, the oil was divided into three types. The oleum omphacium, the best quality, was extracted from olives that were still green and was produced in September. It was mainly used for religious offerings and the manufacture of perfumes that, centuries before the incorporation of alcohol, used the oil as a base. In the words of Pliny, "the best [oil] of all is given by green olives that have not yet begun to ripen; this is of excellent taste. The more mature the olive is, the greasier and less pleasant the juice". The oleum viride was made in December, with olives varying between green and black. It was a softer and more fruity oil. Finally, oleum acerbum was made from olives that had fallen to the ground and were therefore of inferior quality.

The intermediate category, i.e. oleum viride, which was the most widely used in gastronomy, could be divided into three varieties according to its quality: oleum flos was the virgin oil obtained with the first pressing, which could be compared to our extra virgin oil; oleum sequens was an inferior quality oil, as it was obtained with a second, more intense pressing; and finally, oleum cibarium, the most ordinary of the three, came from the following pressing.

Oil in all dishes

As is the case today in the so-called "Mediterranean Diet", oil was a fundamental element of the Roman diet. Apicius, in his famous recipe book De re coquinaria, names the oil in more than three hundred recipes. It could be used for seasoning, cooking and frying. It was also a basic ingredient in the preparation of sauces; although these varied according to the type of food they accompanied, they all had oil in common. For example, for boiled meat Apicius recommends a white sauce composed of "pepper, garum, wine, rue, onion, pine nuts, aromatic wine, a little macerated bread to thicken and oil". In addition, before serving a dish at the table, whether it is based on fish, meat, vegetables or legumes, it was common to sprinkle it with a few drops of oil. This also had a place in pastries. Apicio gives us the formula for a "dish that can be used as a sweet": "Toast pine nuts, peeled walnuts; mix with honey, pepper, garum, milk, eggs, a little pure wine and oil".

An indication of the importance of oil in the Roman diet is that Julius Caesar incorporated it into the annona, a free supply of grain that was given to the army for maintenance. From then on, the demand for oil increased greatly. The presence of this product among the soldiers stationed at the northern border of the Empire indicates that the peoples of Central and Northern Europe were incorporating it into their diet.

Ointments and perfumes

Oil had other fundamental uses in the daily life of the Romans. On the one hand, it was used as fuel for lighting. The Romans used hollow, molded skylights that were filled with the worst quality olive oil. This soaked a wick of vegetable fibers, such as spun linen or papyrus, which could thus be kept burning for a long time.

The oil was also used as an ointment; hence Pliny's phrase "wine on the inside and oil on the outside". Those who practiced physical exercise in the baths anointed their bodies with oil before training in the arena or gymnasium. In this way they protected their skin from the sun and moisturized it. After training, they cleaned their bodies with a strigil, a curved bronze tool that allowed them to remove the layer of oil, dust and accumulated sweat. Although it is hard to believe, this mixture was very popular and the directors of the gyms sold it for medicinal uses. As Pliny explained, "It is known that the magistrates who were in charge [of the gymnasium] sold the oil scrapes for eighty thousand sesterces”. The athlete's equipment therefore included one or more strigils and a small bottle, also made of bronze or glass, in which to store the oil.

Not only did the athletes use it; the oil was also applied as a body moisturizer and as an ointment to heal wounds. In medicine it could be used alone or as an excipient, and was prescribed to treat ulcers, calm colic or lower fever. Ointments, a type of perfumed oil associated with cosmetics and perfumery, spread among Roman society from the second century B.C. They were not only based on olive oil, but could also use other types of oil such as almond, laurel, nut or rose oil. The deceased were also anointed with these perfumed oils, which is why small glass ointments were a common object in funeral trousseaux.

Source: National Geographic